I wanted to make a brief post about GPS and how it works; hopefully, it will increase your knowledge as it has mine.

Now, I know what you’re thinking, “Well, Lee I know how GPS works, you use three satellite’s signal to triangulate your position”. No. Well yeah, but hold on.

Maybe the more informed would say, “GPS satellites use atomic clocks and transmit their time down to the earth. A receiver would then receive this signal and synchronize it to step in sequence with the clock. Using the time drift between the three or however many satellites visible, a receiver can approximate your location using the drift between your receiver’s clock and each of the onboard clock of the satellite”. Ya’ll go fuck off to your fancy universities and talk about how the world is caving in on itself because communism failed thirty years ago in front of a greco roman painting. No one likes you.

But what I’d like to do is get more into the nitty-gritty waves and bits of GPS to understand it. Anyone can have a surface level understanding of a topic but until the open it, and work on it, the information they know or think they know can be flawed. With that watch me make a fool of myself.

So lets first talk about the waveform, for this section I will be heavily leaning on this post for information if you’d like to read that instead be my guest.

Here is the formula for generating a GPS signal (at least in the L1 band but we’re gonna keep things simple).

\[\begin{equation} s^{\text{(GPS L1)}}_{T}(t)=e_{L1I}(t) + j e_{L1Q}(t)~, [1] \end{equation}\]All this formula says is that your signal, your signal being a complex value (i.e composed of both a real and imaginary value), at time t is equal to the functions \(e_{L1I}(t)\) and \(e_{L1Q}(t)\). These functions are further described below.

\[\begin{equation} e_{L1I}(t) = \sum_{l=-\infty}^{\infty} D_{\text{NAV}}\Big[ [l]_{204600}\Big] \oplus C_{\text{P(Y)}} \Big[ |l|_{L_{\text{P(Y)}}} \Big] p(t - lT_{c,\text{P(Y)}})~, [2]\end{equation}\] \[\begin{equation} e_{L1Q}(t) = \sum_{l=-\infty}^{\infty} D_{\text{NAV}}\Big[ [l]_{20460} \Big] \oplus C_{\text{C/A}} \Big[ |l|_{1023} \Big] p(t - lT_{c,\text{C/A}})~,[] 3]\end{equation}\]Here is where the real meat and potatoes of GPS is. Just to emphasize how great these three lines are lemme just rant for a second.

In the world today there are about 3.6 billion GNSS devices in use. The GPS generates about $1.4 trillion dollars (2017) in economic benefits since it was made (thats capitalist speak for GPS == mad dosh). The loss of GPS would result in about $1 billion dollars per day. There isn’t an industry in the world that doesn’t rely on GPS in some way. For something so hugely instrumental in our global economic infrastructure here it is discribed before you in effectively three lines. Three fucking lines. They have more impact in the world in an hour than I will in my lifetime. And it keeps me up at night. Back on topic.

Let us break down each formula and understand what’s happening. Not everyone was born with a degree in mathematics so it can pretty scary to see all these greek symbols. I’m told mathematicians were often burned at the stake in the 1950s because of their formulas and postulates.

Alright, formula one essentially breaks down the GPS baseband signal in terms of complex values (in-phase and quadrature/real and complex values). Equation two generates the I component while Equation three generates the Q component. If you’re confused about what I&Q values are, a picture’s worth a thousand words, so a gif is like a million.

Both equations are functionally equivalent except for one very large difference which we’ll come to later. For now, we’ll fixate on function three. \(D_{\text{NAV}}\) is the navigation message sequence, \(C_{\text{C/A}}\) is the Coarse Code or Gold Code sequence. The signal \(p(t)\) is a rectangular pulse starting a t=0 and lasting the duration of the chip period. Honestly \(p(t)\) isn’t really that important

The Coarse code is a pseudorandom sequence that is generated with two linear feedback shift registers. The coarse code is then xor’d with the navigation code ‘spreading’ the data out. The code below effectively models the C/A generator for a GPS satellite.

#https://natronics.github.io/blag/2014/GPS-prn/

def shift(register, feedback, output):

"""GPS Shift Register

:param list feedback: which positions to use as feedback (1 indexed)

:param list output: which positions are output (1 indexed)

:returns output of shift register:

"""

# calculate output

out = [register[i-1] for i in output]

if len(out) > 1:

out = sum(out) % 2

else:

out = out[0]

# modulo 2 add feedback

fb = sum([register[i-1] for i in feedback]) % 2

# shift to the right

for i in reversed(range(len(register[1:]))):

register[i+1] = register[i]

# put feedback in position 1

register[0] = fb

return out

G1 = [1]*10

G2 = [1]*10

ca = [] # stuff output in here

# create sequence

for i in xrange(1023):

g1 = shift(G1, [3,10], [10])

g2 = shift(G2, [2,3,6,8,9,10], [2,6]) # <- sat chosen here from table

# modulo 2 add and append to the code

ca.append((g1 + g2) % 2)

# return C/A code!

print(ca)

After the code is generated it is then xor’d with the navigation data, spreading the signal out. Each bit for the nav code is \(0.02s\) in length while each bit for the C/A is about \(1 / 10.23 \mu s\). So to cover or spread a navigation bit the entire C/A sequence is xor’d with a single navigation bit two hundred times, resulting in a chip sequence (chips are bits after they’ve been spread) 204600 chips in length. Python for the programically minded.

nav_bit = 1

chip_sequence = []

for _ in range(0, 200):

for i in range(0, 1023):

x = ca[i] ^ nav_bit

chip_sequence.append

The chip_sequence array is essentially a GPS signal, at least from the civilian perspective, we will talk about why in a minute. For now let’s move on to why we spread the signal.

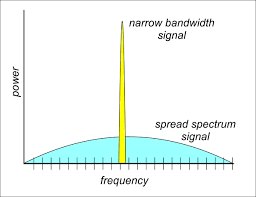

First each satellite is talking constinuously on the same band. To share the same medium at the same time and frequncy, we must multiplex the signal in some way. Normally what transmitters do it either Time Division Multiplexing, where you transmit and then let someone else transmit on the same frequency, or Frequency Division Multiplexing, where you transmit at one frequency and everyone else transmits at other frequency, but these methodologies don’t fit our requirements. So, what GPS instead uses is called CDMA, Code Division Multiple Access. What happens is the signal power is actually ‘spread’ by the spreading code (go figure), so instead of having a loud, small signal, we have a very quiet, wide signal. GPS operates near the noise floor partly because of the huge spreading factor and because each GPS satellite uses full-earth omnidirectional antennas (newer satellites are being equipped with directional antennas to provide a GPS ‘spotlight’).

The reason it widens in bandwidth is because we’re changing bits around faster resulting in our frequency varying more and more. Now using more bandwidth sounds like we’re making the problem worse instead of better, but what we can do here is give each satellite a C/A code that is orthogonal to all the other satellite’s C/A. What this means is that at time t, each and every satellite is transmitting at a different frequency in the band, so they’re not stepping on each other’s transmission. If you look back at our code, the second LFSR uses bits [2,6] to determine it’s output, but this varies satellite to satellite so that each PRN is unique (the lookup table for each satellite’s LFSR configuration can be found here at pg. 5).

Second, the spreading code allows our receiver to do is synchronize with the satellite’s onboard clock. Because the GPS signal repeates the same sequence 200 times per navigation bit, it allows the receiver to blindly be able to determine which satellite it is and determine what information it is sending by brute force. Refering back to the equation two, the function \(C_{\text{P(Y)}}\) generates a precision code that’s only allowed for military use. The timing on the Precision code is much smaller, allowing for a higher fidelity synchronization and thus a better location fix. Since the P(Y) code is exclusively used for the military, equation two and subsequently the I component for GPS is dead to us, meaning we can simplify formula down to just this:

\[\begin{equation} s^{\text{(GPS L1)}}_{T}(t)= 0 + j\sum_{l=-\infty}^{\infty} D_{\text{NAV}}\Big[ [l]_{20460} \Big] \oplus C_{\text{C/A}} \Big[ |l|_{1023} \Big] p(t - lT_{c,\text{C/A}})~ \end{equation}\]So hopefully now we understand the C/A code, let’s talk a little about the navigation data. The navigation message includes several pieces of data:

- Orbit parameters (aka ‘broadcast ephemeris’), which is basically the satellite’s location in space.

- Time and clock bias parameters, useful for correcting clock errors at the receiver

- Almanac Data, contains the overal status and location of GPS constellation

- Satellite halth status

- Some other odds and ends.

The data like the almanac is useful for receivers because it can store that information for a warm start, so it estimate the satellite’s position and acquire’s them faster when trying to get a lock. But all we need is the ephemeris data from multiple satellites to figure out our position.

So let’s tie this all together. When we synchronize with a satellite, we’re synthetically reproducing the satellite’s signal internally in the receiver. We receiving the actual GPS signal, then looking at the delta between the two. This delta allows us to figure out our distance from the GPS satellite. Combining the ephemeris data along with the delta/distance from multiple satellites allows us to triangulate our position (sorta like in CSI).

And that’s all there is to it. Are you smarter? I am.

Fin.